Question: Information provided by a set of financial statements is essential to any individual analyzing a business or other organization. The availability of a fair representation of a company’s financial position, operations, and cash flows is invaluable for a wide array of decision makers. However, the sheer volume of data that a company such as General Mills, McDonald’s, or PepsiCo must gather in order to prepare these statements has to be astronomical. Even a small enterprise—a local convenience store, for example—generates a significant quantity of information virtually every day. How does an accountant begin the process of accumulating all the necessary data so that financial statements can eventually be produced?

Answer: The accounting process starts by analyzing the effect of transactions—any event that has a financial impact on a company. Large organizations participate in literally millions of transactions each year that must be gathered, sorted, classified, and turned into a set of financial statements that cover a mere four or five pages. Over the decades, accountants have had to become very efficient to fulfill this seemingly impossible assignment. Despite the volume of transactions, the goal remains the same: to prepare financial statements that are presented fairly because they contain no material misstatements according to U.S. generally accepted accounting principles .

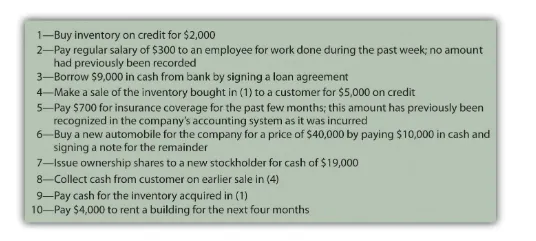

For example, all the occurrences listed in Figure 4.1 “Transactions Frequently Encountered” are typical transactions that any company might encounter. Each causes some measurable effect on a company’s assets, liabilities, revenues, expenses, gains, losses, capital stock, or dividends paid. The accounting process begins with an analysis of each transaction to determine the financial changes that took place. Was revenue earned? Did a liability increase? Has an asset been acquired?

In any language, successful communication is only possible if the information to be conveyed is properly understood. Likewise, in accounting, transactions must be analyzed so their impact is understood. A vast majority of transactions are relatively straightforward so that, with experience, the accountant can ascertain the financial impact almost automatically. For transactions with greater complexity, the necessary analysis becomes more challenging. However, the importance of this initial step in the production of financial statements cannot be overstressed. The well-known computer aphorism captures the essence quite succinctly: “garbage in, garbage out.” There is little hope that financial statements can be fairly presented unless the entering data are based on an appropriate identification of the changes created by each transaction.

Transaction Analysis

Question: Transaction 1—A company buys inventory on credit for $2,000. How does transaction analysis work here? What accounts are affected by this purchase?

Answer: Inventory, which is an asset, increases by $2,000. The organization has more inventory than it did prior to the purchase. Because no money has yet been paid for these goods, a liability for the same amount has been created. The term accounts payable is often used in financial accounting to represent debts resulting from the acquisition of inventory and supplies.

inventory (asset) increases by $2,000

accounts payable (liability) increases by $2,000

Note that the accounting equation described in the previous chapter remains in balance. Assets have gone up by $2,000 while the liability side of the equation has also increased by the same amount to reflect the source of this increase in the company’s assets.