Question: In a periodic inventory system, a physical count is always taken at or very near the end of the fiscal year. This procedure is essential. There is no alternative method for determining the final inventory figure and, hence, the cost of goods sold for the period. When a company uses a perpetual system, is a count of the goods on hand still needed since both the current inventory balance and cost of goods sold are maintained and available in the accounting records?

Answer: A physical inventory is necessary even if a company has invested the effort and cost to install a perpetual system. Goods can be lost, broken, or stolen. Errors can occur in the record keeping. Thus, a count is taken on a regular basis simply to ensure that the subsidiary and general ledger balances are kept in alignment with the actual items held. Unless differences become material, this physical inventory can take place at a convenient time rather than at the end of the year. For example, assume that a company sells snow ski apparel. If a perpetual system is in use, the merchandise could be inspected and counted by employees in May when quantities are low and damaged goods easier to spot.

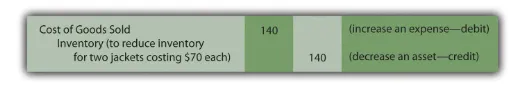

An adjustment is necessary when the count does not agree with the perpetual inventory balance. To illustrate, assume that company records indicate that sixty-five ski jackets are currently in stock costing $70 apiece. The physical inventory finds that only sixty-three items are actually on hand. The inventory account must be reduced (credited) by $140 to mirror the shortfall (two missing units at $70 each).

The other half of the adjusting entry depends on the perceived cause of the shortage. For example, officials might have reason to believe that errors took place in the accounting process during the period. When merchandise is bought and sold, recording miscues do occur. Possibly two ski jackets were sold on a busy afternoon. The clerk got distracted and the cost of this merchandise was never reclassified to expense. This type of mistake means that the cost of goods sold figure is too low. The balance reported for these two jackets needs to be moved to the expense account to rectify the mistake.

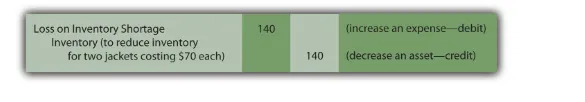

onversely, if differences between actual and recorded inventory amounts occur because of damage, loss, or theft, the reported balance for cost of goods sold should not bear the cost of these items. They were not sold. Instead, a loss occurred.

If the assumption is made here that the two missing jackets were not sold but have been lost or stolen, the following alternative adjustment is appropriate.

n practice, when an inventory count is made and the results differ from the amount of recorded merchandise, the exact cause is often impossible to identify. Whether a loss is reported or a change is made in reporting cost of goods sold, the impact on net income is the same. The construction of the adjustment is often at the discretion of company officials. Normally, consistent application from year to year is the major objective.

Question: A periodic system is cheap and easy to operate. It does, though, present some practical problems. Assume that a company experiences a fire, flood, or other disaster and is attempting to gather evidence—for insurance or tax purposes—as to the amount of merchandise that was destroyed. How does the company support its claim? Or assume a company wants to produce interim financial statements for a single month or quarter (rather than a full year) without going to the cost and trouble of taking a complete physical inventory count. If the information is needed, how can a reasonable approximation of the inventory on hand be derived when a periodic system is in use?

Answer: One entire branch of accounting—known as “forensic accounting”—specializes in investigations where information is limited or not available (or has even been purposely altered to be misleading). For example, assume that a hurricane floods a retail clothing store in Charleston, South Carolina. Only a portion of the merchandise costing $80,000 is salvaged1. In trying to determine the resulting loss, the amount of inventory in the building prior to the storm needs to be calculated. A forensic accountant might be hired, by either the owner of the store or the insurance company involved, to produce a reasonable estimate of the merchandise on hand at the time. Obviously, if the company had used a perpetual rather than a periodic system, the need to hire the services of an accounting expert would be less likely unless fraud was suspected.